Studio David Claerbout just published the video of a lecture at The Cloud Collection, Nanjing on the occasion of the opening “Flow of Time. David Claerbout and Zhou Tao” exhibition.

At 17:50, he explains how he made the Woodcarver and the Forest. Prompting ChatGPT to create a script and images, then filming what ChatGPT suggested, and then giving it back to ChatGPT and asking whether it recognises itself.

I took the rough auto-generated YouTube transcript of this talk, and prompted ChatGPT as follows: “take this transcript, delete the time markers, delete the uhm’s, and put it together in readable sentences”, and this is what it came up with (highlights by Petervan)

+++ by ChatGPT

Thank you for coming. When the invitation arrived to make a double exhibition with the work of Zhou Tao, we were of course very curious. It was clear that there was a real reason we were invited to exhibit together, but there was also a lot of mystery because I didn’t know his work very well, and I had not yet realized the intrinsic relationship to time in his work. It was only by coming here a few days ago that it started to sink in—what the subtle relationships between the two of us might be.

First of all, I would like to thank the Cloud Collection for bringing us together. We obviously have very different ways of working, which you can see in the works. For Joe, being in a location, being physically in a place with his camera as his partner, is crucial. In my practice, we spend a long time and work with many people, sometimes for at least a year. If I look around at the pieces in this exhibition, I think the shortest production time is one full year. Other works took two or three years. Our record, if I remember well, is sixteen years—sixteen years of thinking back and forth about how to do something until we finally finished a production.

What we do have in common is that we like to use the duration of the film as the acting force—not so much the actors, not so much the motives, but the simple fact of being in front of a situation. This approach to film is relatively recent and has to do with the availability of digital time. I call it digital time because it is no longer expensive time; it’s virtual time of which we can gather a lot. For our generation, duration is no longer exclusive, expensive, or spectacular, but something broad and long.

When I came here two days ago and saw the combination with the work of Tao, it made me question myself: is it really necessary that I work so long on a single image? The airplane is a single motive. The birdcage is a single motive. These works revolve around very simple motives. I have to admit that whenever I work on one film, I am actually thinking about two films. This is one of the reasons I keep my motives simple: because I try to work with two identities.

For example, the film behind you, The Wood Carver, has the identity of a meditative work that calms you down, but also another identity that is almost the complete opposite. I’ve always been fascinated by what happens when you let go of narrative film—when you let go of talkies, psychological realism, and story, and instead go with time, with duration, with the flicker of the images. Could I make a very minimalist film where I use the least possible narrative and still generate narrative inside the heads of the visitors?

As you walk around, you’ll notice there are few sounds—no soundtracks, only what I call “witness sounds”: bird songs, nature, wind, footsteps. It wasn’t always like this. I made films with soundtracks, musical scores, conversations between actors. But my focus was always on the background, and more and more the birds became a symbol for that background—giving the film back to the witnesses rather than the actors. In cinema we often speak about foreground and background, like in painting. I realized I have a preference for what is behind—for what is far away, not in the foreground.

One of my very first films, made in 2003, is a 14-hour film where three actors perform a short 12-minute scene repeatedly for a full day, until they start making errors or falling apart. Only then do you slowly begin to see that the film is really about the light, the changes of light, and not about the narrative in the foreground. I am very much an advocate of the cinema of the witness, not the cinema of the actor.

A word also on ecology: I avoid entering specific subject matter, but I cannot help noticing that we spend a lot of time in front of screens and very little in nature. This makes me think about the relationship we have with technology. On one hand, I love technology—I’m a technological buff, and whenever something new appears, I try to catch up with it. But at the same time, my works are not about technology. They are about light and shadow, about composition, about the slow pace of time. Again, there are two tracks.

Any cinematographer knows that the moving image is a technological construction—25 frames per second. It is a prison of time; you cannot escape it. So why would artists choose to work in this prison in order to liberate time? To find alternatives for thinking about the flow of time, as Suzu beautifully mentioned in his text.

Let me elaborate on the black-and-white film behind the wall, titled Aircraft Final Assembly Line. Like many of my films, it is based on an image or an idea I found somewhere—an archive image, something with no particular message. I found a black-and-white photograph of this aircraft. It was originally painted in black matte aluminum. I was fascinated by the enormous wooden hall in Chicago where it was constructed—a space that no longer exists. This polished aluminum aircraft stood there, brand new in the past, yet I look at it now from the future, as a witness. I know the aircraft is probably destroyed by now. The work became about the dialectic between materials: polished aluminum, rough wood, concrete floor, improvised-looking scaffolding—yet airplanes themselves are not improvised. They must be perfect. Airplanes are like perfect arrows of time: they promise the future.

This is typical of how I work: I don’t invent; I let myself be inspired by archive images, almost orphaned images from the past.

When we move mentally to Bird Cage, the film with the explosion, this was a follow-up to a pandemic-era film, Wildfire. I continued with the motive of the explosion because it is the perfect index of a moment—after an explosion, nothing is ever the same. I was fascinated by the idea of remaining inside that moment of change for a long time, looking at all the pieces of the world flying apart, but in a peaceful way. Again, a paradox between destructive and meditative energies.

In the middle of this are two birds that appear twice—once inside the explosion, at the last fraction of their lives, and again later, alive and peaceful in a garden. I hesitated for a long time to use this imagery because it is almost ridiculous—two birds in an explosion, like a crucifix of birds. But I kept it because I was fascinated by the elliptical camera movement. If you look closely, there is no cut: the camera moves from the explosion back to a normal, sunlit garden, with the same two birds sitting together, almost as if they are trying to tell you something. Ten minutes later, the same ellipse brings you back to the explosion, frozen in time—an “immobile explosion,” a contradiction in itself.

I like to work within a single mental space, not jumping between spaces but taking the viewer on a minimalist journey through one situation.

The confetti piece around the corner, the double screen, was made from 2016 to 2018. It corresponds to a series I’ve done for about 15 years: dozens or hundreds of digitally constructed photographs combined into a slideshow. A conventional parade of images, except that it’s about the absence of sound. In the film, a little boy is screaming, but you hear nothing. His scream becomes internalized. The scene is exaggerated—a Black boy surrounded by white adults. I was warned against using it because it might appear divisive. But I said yes, that tension is exactly what we need in order to reach something more universal. The real fascination for me was the internalized scream, and the way spending time with the work might let the viewer internalize it too. It is as close as I can get to a painting with an action attached to it.

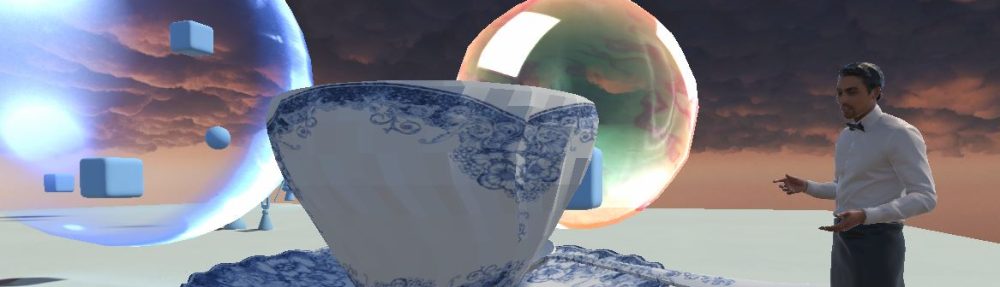

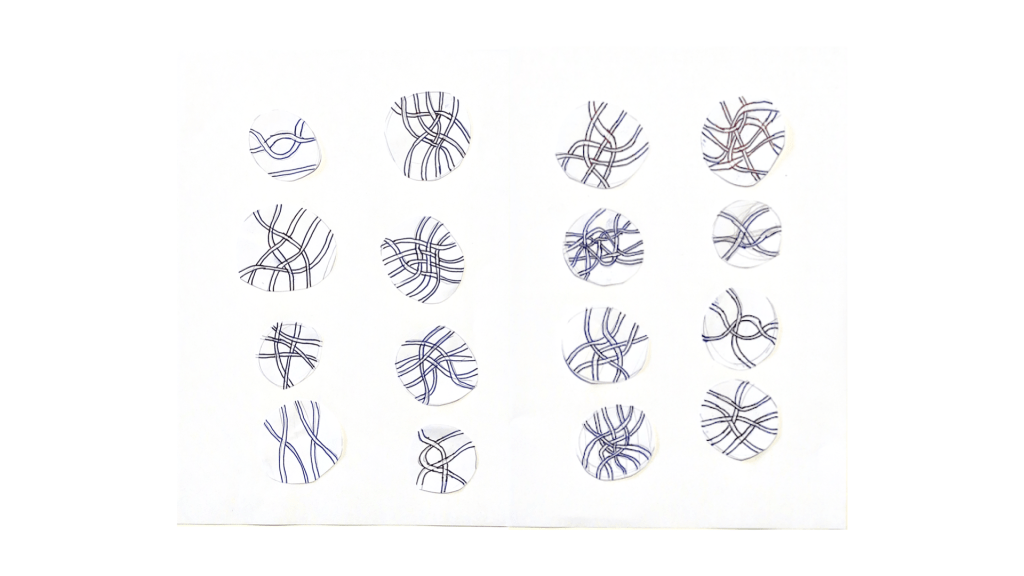

Finally, behind us is the latest work we made, just finished for this exhibition: The Wood Carver in the Forest. The subtitle is “A ruthless deforestation machine disguised as a meditative film.” Again, it has two identities. Most spectators will identify with the relaxation—the small sounds, the details of oil, wood, knives, carving, micro-movements outside any big narrative.

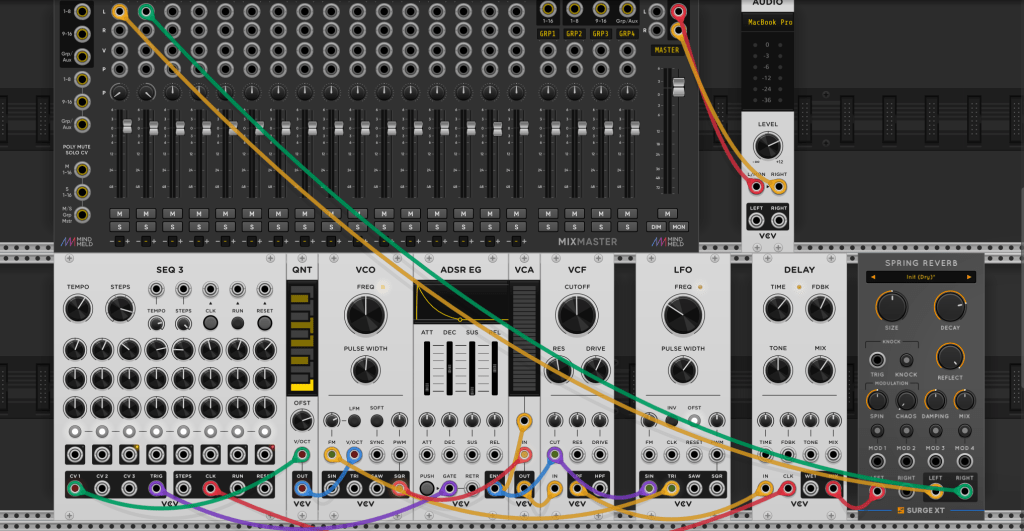

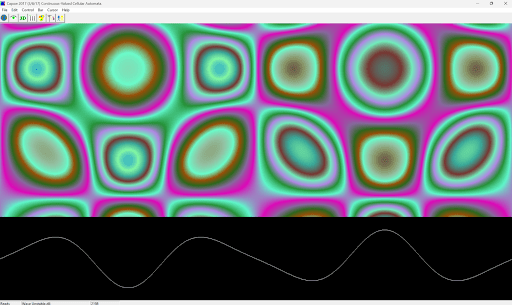

We designed this work using ChatGPT. ChatGPT is one big confabulation machine; it always gives you an answer, even when it has no clue. We wrote the storyboard with it, then requested illustrations, and used those as the basis for a cinematographic team. We worked for a year to reproduce what AI had suggested.

It came up with scenes like the one by the window: a person staring at nature but actually staring at something artificial—as if looking at a screen. In the images, if you look carefully, the “trees” outside are actually vertically stacked television screens. We prompted an image of the garden and it produced about ninety trees. Using its own calculation, it estimated it would take thirteen years for the protagonist to turn those trees into wooden objects. From those “thirteen years,” we selected three days—one early, one mid-process, one at the end—and produced only those.

In the end, it becomes a loop: AI proposes something, we produce it, then return it to AI like an alien creature and ask, “Do you recognize yourself?” About 5–7% of the imagery is completely fake—AI reprocessing its own outputs.

The idea of the work is that someone else—not me—could complete those thirteen years of destruction. My job was to create images with two simultaneous identities, properly schizophrenic: destructive and generative at the same time.

I think I will stop here. Thank you.

+++ end ChatGPT