Petervan’s Musical Ride December 2025 – only 39 songs. As usual, mostly several recent releases, including those by Selah Sue, Tackhead, and Tsar B. Oldies from Chris Rea, Gary Claill, and The Durutti Column. Play in shuffle mode to increase the surprise factor. Enjoy!

Monthly Archives: December 2025

The Orphic Experience: We are all Argonauts again

In my post about Dub-Techno artist Adrian Sherwood, I referred to the book “Dub Techno – The Orphic Experience of Sound” by Bahadırhan Koçer to describe my sound experiments with dub.

As promised in that post, the most compelling part of the book appears in its opening chapters, where he introduces “The Orphic Experience.”

The short summary is in the video below, from 0:59 to 2:23. The latter part of the video is about the three key elements of dub-techno: spontaneous repetition, atmosphere, and embracing noise.

TL;DR: The orphic experience uses music to alter perception, evoke deep emotions, and influence the listener’s state of mind. It creates a unique space and time for introspection and reflection.

Let me unpack this in stages: first the “orphic” aspect, then the “experience” element, and finally a synthesis.

Orphic

The “orphic” part originates from Orpheus, a character in the ancient Greek poem Argonautica, dating back to the 3rd century BC. The Argonauts are travellers on the boat Argo and are on a quest for the golden fleece. Somewhere along the route, sirens are trying to seduce the boatsmen. Still, Orpheus – a talented singer/musician on the boat – can shield the boatsmen from the Sirens’ temptations through his celestial, beautiful songs and voice. In other words, he was a noise canceller avant la lettre.

Some salient quotes from Bahadırhan Koçer:

The orphic experience, therefore, refers to the transformative way sound and media technologies can be used to control one’s sonic environment, creating a personalized auditory space that shields individuals from the overwhelming stimuli of modern life.

It is conceivable to argue that the nature of this transformation lies fundamentally in a shift from communal to individual listening.

The protected space needed for “sensory and emotional self-care”

In this sense, orphic experience can be seen as a way of escaping from the demands of the real world and constructing a self-contained, artificial reality.

By carefully curating their auditory environment and creating a personalized soundtrack to their lives, the individual can signal their taste and distinction to others, and distinguish themselves from those who do not possess the same level of cultural capital.

The “orphic” concerns the creation of a protected, isolated space in which the rules constraining clear thought can be suspended.

Experience

The second part is about “experience”. The words “Narrative” and “Experience” have become catch-all words. Washed-out. Weak. And they all suggest a passive audience.

Also here, a David Claerbout quote is appropriate:

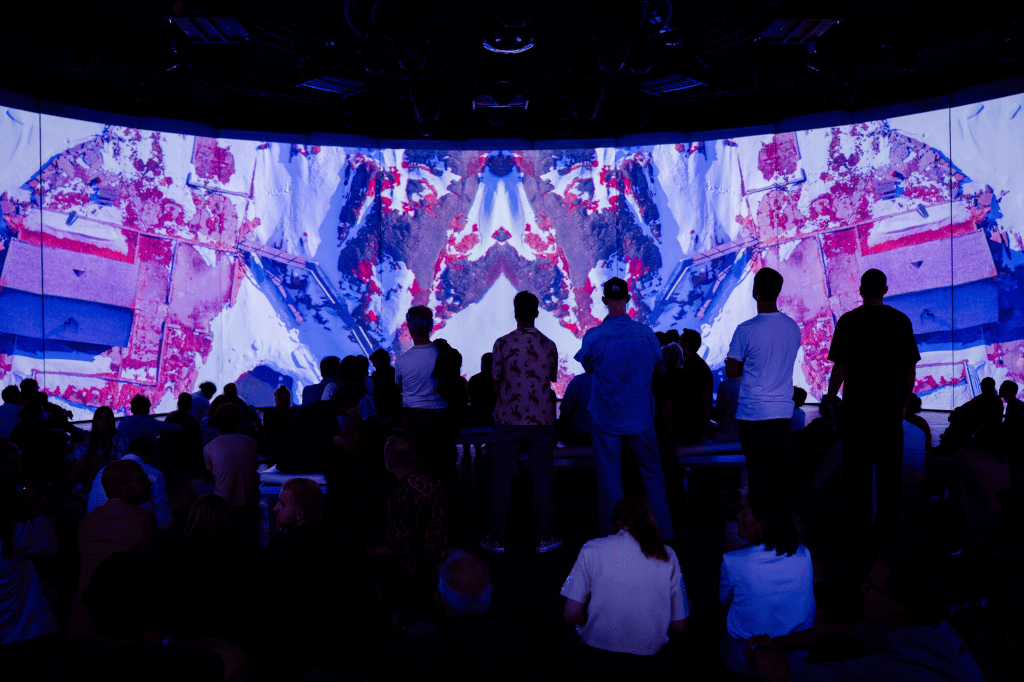

“I think the recent proliferation of black boxes for film and video-art is not just a practical solution to a problem of sound and light interference, but also reflects an incapability to coexist. This can become apparent in large group exhibitions, where media installations appear strong when they are shown by themselves in a small or large dark space, but they easily collapse when shown in a social space where people move about and interact. The black box is a social phenomenon, for me it is a problem.” Ulrichs, David, ‘David Claerbout. Q/A, in: Modern Painters, May 2011, pp. 64-66

“Designed Conspiracy” would be better to describe what I have in mind. With an active audience. Or even better, where there is no stage hosting the expert speaker and no passive audience just leaning back in chairs, incapable of truly internalising knowledge.

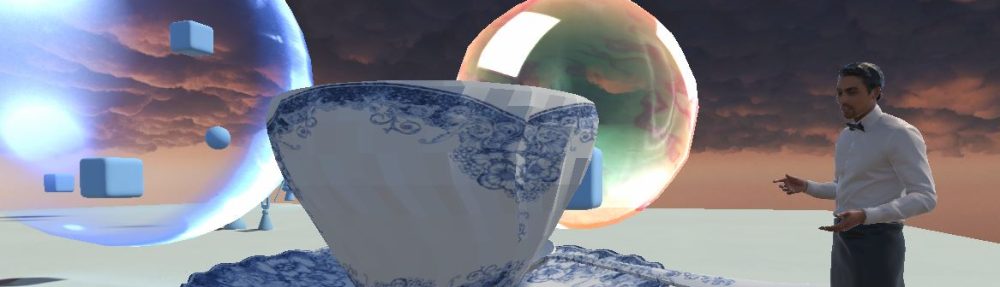

I imagine us inside a 360° immersive room: a six-metre-high LED screen, full 360 Dolby Atmos sound, LiDAR tracking, and high-definition cameras—paired with exceptional content and facilitation. A complete experience in a box, ready to tour and deploy anywhere in the world. Am I exaggerating? Maybe not. I’ve just met someone who is building exactly this.

Synthesis

Obviously, I am using all of the above as a metaphor to try to explain what I do with my artistic interventions, provocations, and interruptions. These qualities inform my work/play. Whether that is soundscapes, installations, performances, or group expeditions.

Now that we have our protected, isolated space and a designed conspiracy, it is time to play the music. Music is the content. Content is the music.

Experiencing our music – individually or as part of a group – can feel like a trip, a trance, like digital psychedelics.

The music/content is presented in the right space, with the appropriate emotional and psychological atmosphere—the backdrop, if you will—inviting and sustaining safety, interest, curiosity, awe, and growth.

The rhythm is softer, slower, quieter vs. harder, faster, louder.

We embrace – and even design – flaws and imperfections, spontaneous repetition, and noise, inviting the participants to connect with being human, and to internalise the content at an embodied level of sensory experience.

We design with fifty shades of sophistication: avant-garde activism shaped by counterculture, driven by intention and direction. We build a relational infrastructure capable of holding shared ambitions, carrying a map as a symbol of movement, of becoming. These are maps that make meaning—shifting the question from the adolescent “Where are we going?” to the more deliberate “What direction do we want?”

We are all Argonauts again. We are experiens-explorers. We want to create the right spaces and conditions for debating the new rules and the associated structures of reality, then acting them out as if those rules were in place. As explorers, we want to play with new rules to dream, new rules to hope, but also – not to sound too cheesy or utopian – new rules to suffer and cope with what is evil and sin. In that sense, we become all part of a shared conspiracy.

We are not in the business of homo sapiens, ludens, or faber, but in the business of homo experiens.

With thanks to my co-conspirators Josie and Andreea, for challenging me over and over again

Inspiration – Even more David Claerbout

Studio David Claerbout just published the video of a lecture at The Cloud Collection, Nanjing on the occasion of the opening “Flow of Time. David Claerbout and Zhou Tao” exhibition.

At 17:50, he explains how he made the Woodcarver and the Forest. Prompting ChatGPT to create a script and images, then filming what ChatGPT suggested, and then giving it back to ChatGPT and asking whether it recognises itself.

I took the rough auto-generated YouTube transcript of this talk, and prompted ChatGPT as follows: “take this transcript, delete the time markers, delete the uhm’s, and put it together in readable sentences”, and this is what it came up with (highlights by Petervan)

+++ by ChatGPT

Thank you for coming. When the invitation arrived to make a double exhibition with the work of Zhou Tao, we were of course very curious. It was clear that there was a real reason we were invited to exhibit together, but there was also a lot of mystery because I didn’t know his work very well, and I had not yet realized the intrinsic relationship to time in his work. It was only by coming here a few days ago that it started to sink in—what the subtle relationships between the two of us might be.

First of all, I would like to thank the Cloud Collection for bringing us together. We obviously have very different ways of working, which you can see in the works. For Joe, being in a location, being physically in a place with his camera as his partner, is crucial. In my practice, we spend a long time and work with many people, sometimes for at least a year. If I look around at the pieces in this exhibition, I think the shortest production time is one full year. Other works took two or three years. Our record, if I remember well, is sixteen years—sixteen years of thinking back and forth about how to do something until we finally finished a production.

What we do have in common is that we like to use the duration of the film as the acting force—not so much the actors, not so much the motives, but the simple fact of being in front of a situation. This approach to film is relatively recent and has to do with the availability of digital time. I call it digital time because it is no longer expensive time; it’s virtual time of which we can gather a lot. For our generation, duration is no longer exclusive, expensive, or spectacular, but something broad and long.

When I came here two days ago and saw the combination with the work of Tao, it made me question myself: is it really necessary that I work so long on a single image? The airplane is a single motive. The birdcage is a single motive. These works revolve around very simple motives. I have to admit that whenever I work on one film, I am actually thinking about two films. This is one of the reasons I keep my motives simple: because I try to work with two identities.

For example, the film behind you, The Wood Carver, has the identity of a meditative work that calms you down, but also another identity that is almost the complete opposite. I’ve always been fascinated by what happens when you let go of narrative film—when you let go of talkies, psychological realism, and story, and instead go with time, with duration, with the flicker of the images. Could I make a very minimalist film where I use the least possible narrative and still generate narrative inside the heads of the visitors?

As you walk around, you’ll notice there are few sounds—no soundtracks, only what I call “witness sounds”: bird songs, nature, wind, footsteps. It wasn’t always like this. I made films with soundtracks, musical scores, conversations between actors. But my focus was always on the background, and more and more the birds became a symbol for that background—giving the film back to the witnesses rather than the actors. In cinema we often speak about foreground and background, like in painting. I realized I have a preference for what is behind—for what is far away, not in the foreground.

One of my very first films, made in 2003, is a 14-hour film where three actors perform a short 12-minute scene repeatedly for a full day, until they start making errors or falling apart. Only then do you slowly begin to see that the film is really about the light, the changes of light, and not about the narrative in the foreground. I am very much an advocate of the cinema of the witness, not the cinema of the actor.

A word also on ecology: I avoid entering specific subject matter, but I cannot help noticing that we spend a lot of time in front of screens and very little in nature. This makes me think about the relationship we have with technology. On one hand, I love technology—I’m a technological buff, and whenever something new appears, I try to catch up with it. But at the same time, my works are not about technology. They are about light and shadow, about composition, about the slow pace of time. Again, there are two tracks.

Any cinematographer knows that the moving image is a technological construction—25 frames per second. It is a prison of time; you cannot escape it. So why would artists choose to work in this prison in order to liberate time? To find alternatives for thinking about the flow of time, as Suzu beautifully mentioned in his text.

Let me elaborate on the black-and-white film behind the wall, titled Aircraft Final Assembly Line. Like many of my films, it is based on an image or an idea I found somewhere—an archive image, something with no particular message. I found a black-and-white photograph of this aircraft. It was originally painted in black matte aluminum. I was fascinated by the enormous wooden hall in Chicago where it was constructed—a space that no longer exists. This polished aluminum aircraft stood there, brand new in the past, yet I look at it now from the future, as a witness. I know the aircraft is probably destroyed by now. The work became about the dialectic between materials: polished aluminum, rough wood, concrete floor, improvised-looking scaffolding—yet airplanes themselves are not improvised. They must be perfect. Airplanes are like perfect arrows of time: they promise the future.

This is typical of how I work: I don’t invent; I let myself be inspired by archive images, almost orphaned images from the past.

When we move mentally to Bird Cage, the film with the explosion, this was a follow-up to a pandemic-era film, Wildfire. I continued with the motive of the explosion because it is the perfect index of a moment—after an explosion, nothing is ever the same. I was fascinated by the idea of remaining inside that moment of change for a long time, looking at all the pieces of the world flying apart, but in a peaceful way. Again, a paradox between destructive and meditative energies.

In the middle of this are two birds that appear twice—once inside the explosion, at the last fraction of their lives, and again later, alive and peaceful in a garden. I hesitated for a long time to use this imagery because it is almost ridiculous—two birds in an explosion, like a crucifix of birds. But I kept it because I was fascinated by the elliptical camera movement. If you look closely, there is no cut: the camera moves from the explosion back to a normal, sunlit garden, with the same two birds sitting together, almost as if they are trying to tell you something. Ten minutes later, the same ellipse brings you back to the explosion, frozen in time—an “immobile explosion,” a contradiction in itself.

I like to work within a single mental space, not jumping between spaces but taking the viewer on a minimalist journey through one situation.

The confetti piece around the corner, the double screen, was made from 2016 to 2018. It corresponds to a series I’ve done for about 15 years: dozens or hundreds of digitally constructed photographs combined into a slideshow. A conventional parade of images, except that it’s about the absence of sound. In the film, a little boy is screaming, but you hear nothing. His scream becomes internalized. The scene is exaggerated—a Black boy surrounded by white adults. I was warned against using it because it might appear divisive. But I said yes, that tension is exactly what we need in order to reach something more universal. The real fascination for me was the internalized scream, and the way spending time with the work might let the viewer internalize it too. It is as close as I can get to a painting with an action attached to it.

Finally, behind us is the latest work we made, just finished for this exhibition: The Wood Carver in the Forest. The subtitle is “A ruthless deforestation machine disguised as a meditative film.” Again, it has two identities. Most spectators will identify with the relaxation—the small sounds, the details of oil, wood, knives, carving, micro-movements outside any big narrative.

We designed this work using ChatGPT. ChatGPT is one big confabulation machine; it always gives you an answer, even when it has no clue. We wrote the storyboard with it, then requested illustrations, and used those as the basis for a cinematographic team. We worked for a year to reproduce what AI had suggested.

It came up with scenes like the one by the window: a person staring at nature but actually staring at something artificial—as if looking at a screen. In the images, if you look carefully, the “trees” outside are actually vertically stacked television screens. We prompted an image of the garden and it produced about ninety trees. Using its own calculation, it estimated it would take thirteen years for the protagonist to turn those trees into wooden objects. From those “thirteen years,” we selected three days—one early, one mid-process, one at the end—and produced only those.

In the end, it becomes a loop: AI proposes something, we produce it, then return it to AI like an alien creature and ask, “Do you recognize yourself?” About 5–7% of the imagery is completely fake—AI reprocessing its own outputs.

The idea of the work is that someone else—not me—could complete those thirteen years of destruction. My job was to create images with two simultaneous identities, properly schizophrenic: destructive and generative at the same time.

I think I will stop here. Thank you.

+++ end ChatGPT