I went to the premiere exhibition of David Claerbout’s The Woodcarver and the Forest at the Castle of Gaasbeek. I went by bike, for me, a two-hour ride each way, on a warm sunny day through the Pajottenland, the region southwest of Brussels where I spent the first 25 years of my life. Cycling up and down its rolling hills stirred deep emotions and memories of my youth. This is the land of Bruegel, of Geuze and Lambic beer, of Remco Evenepoel. It is also, unmistakably, my land.

Before arriving at the castle, visitors walk about 15 minutes from the entrance through a carefully tended, forest-like domain. The path itself already feels like part of the experience, drawing you gradually into a slower, quieter, almost meditative state.

There is also a 2-hectare Museum Garden.

A top-level garden modelled on castle gardens from the 18th and 19th centuries. A strong example of living cultural heritage. Take a stroll through this magnificent Garden of Eden, with the old-model fruit repository, the beehives, and a wonderful view of Gaasbeek Castle and the Pajottenland.

I lingered in the garden for some time, sitting on a bench and gazing at another bench across the way, the two connected by a loofgang—a leafy tunnel formed by pear trees. I simply sat in silence, doing nothing. Eventually, I walked through the shaded passage to the other side, before making my way to the castle. In hindsight, the video I captured carries an unintended sense of suspense.

Once inside the castle, visitors are guided along a signposted route. Along the way, I captured this video of sunlight filtering through stained glass, casting vibrant patterns onto the wooden, carpeted floor.

The Claerbout installation awaits at the very end, rising three stories high beneath the roof.

From the brochure:

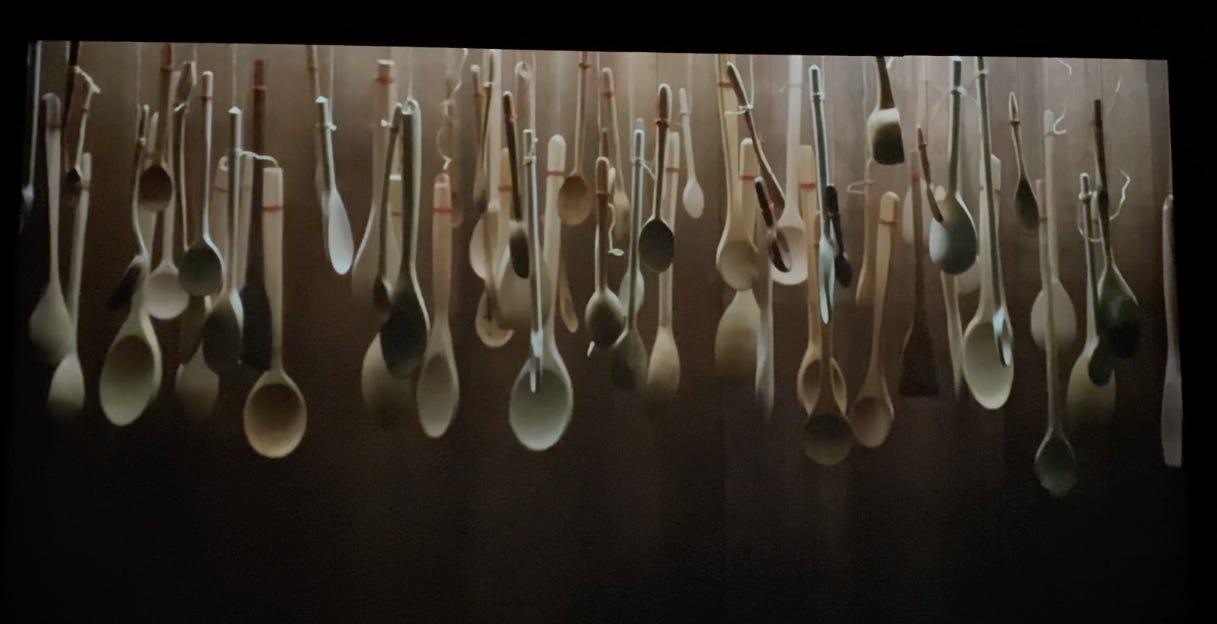

This work is Claerbout’s latest creation and presents itself as an intimate portrait of a reclusive young man. Do you feel the meditative effect of the slow, repetitive movements and their sound?

Specific audiovisual stimuli – such as soft sounds or rhythmic movements – can evoke feelings of relaxation and inner calm. This phenomenon is known as ASMR (Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response) and forms the foundation of this work

The Woodcarver and the Forest is an open film, which is completed using generative artificial intelligence. As a spectator, our experience also remains open and unfinished, partly due to the long duration of the work.

This reveals the dual nature of the film: an interplay between pleasure and sorrow, beauty and destruction.

“I want people to keep watching for hours or at least to settle into that idea of extended time, knowing that they will never be able to see everything.”

I sat in there for more than one hour. It put me in some state of limbo about my own work and where I want to go next. Following Google’s Gemini AI, it means “to be in an uncertain, undecided, or forgotten state where nothing can progress or be resolved, similar to being caught between two stages or places.”

I am a big fan of David Claerbout. See previous entries on this blog here. The Woodcarver gave me the chance to revisit some of Claerbout’s earlier works and conversations, while also helping me reconnect with the artistic drive within myself.

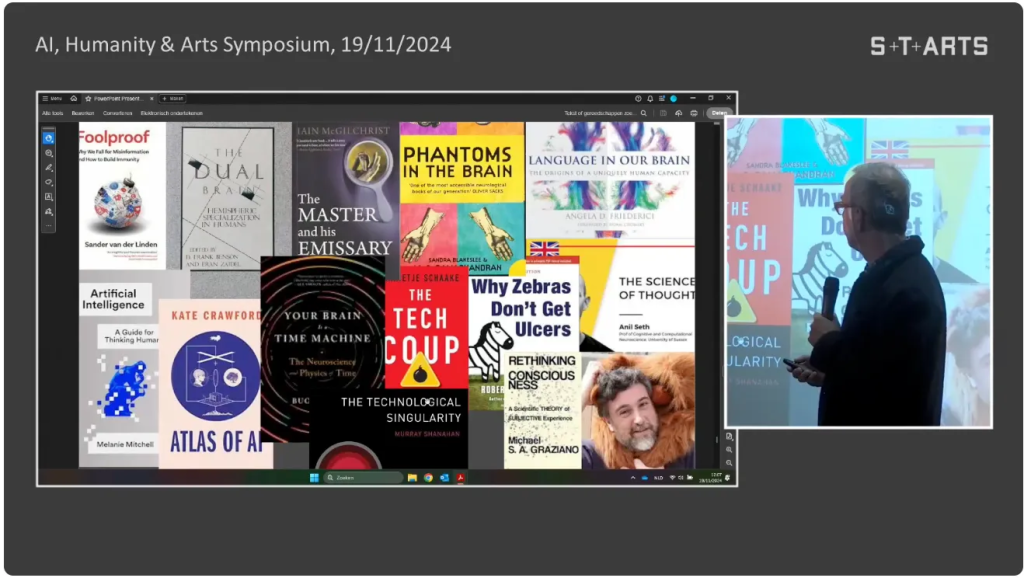

Here is a more recent talk by David Claerbout

Some interesting quotes

Change your mind-set ànd your eye-set, from inquisitive to open-ended

The Brain does not choose sides; it does not know how to

And around minute 18, he gets into a very interesting schema of “former” AI technologies. He really got me when he says “the camera is a profoundly liberal invention” and later “around the 2000s, we start to think of visual culture as a assemblage, the coordinate system is back, and a coordinate system knows exactly where you are it has exact points in space it can find you back and instead of a liberal body in a world that could be anything anywhere it changes into a pinpointing in a space that so we we get a gathering of coordinates and we’re no longer free”

In closing, he shares reflections on recent readings that explore AI, vision, and the language of thought.

After watching the video, I visited the University of Ghent library—you can get a visitor’s pass as a non-student for €15 per year, granting access to all of the university’s libraries! There, I picked up the book The Time That Remains, a title that resonated with me on two levels: first, the concept of time, so ever-present in Claerbout’s work; and second, the realization that I am approaching my seventieth birthday, prompting me to reflect increasingly on the time I have left and how I want to spend it—especially in my artistic practice, if I can even call my tinkering that.

From the intro:

This publication marks the welcome collaboration between internationally acclaimed Belgian artist David Claerbout and two European institutions: Wiels, Brussels and Parasol unit, in London. The publication accompanies Claerbout’s exhibition opening at Parasol unit, on 30 May 2012; but it also provides a highly appreciated documentation for Wiels, which held a solo exhibition of Claerbout’s work, The Time that Remains, in 2011.

It’s from 2012, but the content is, well, timeless.

Some quotes/insights from that book.

“I think the recent proliferation of black boxes for film and video-art is not just a practical solution to a problem of sound and light interference, but also reflects an incapability to coexist. This can become apparent in large group exhibitions, where media installations appear strong when they are shown by themselves in a small or large dark space, but they easily collapse when shown in a social space where people move about and interact. The black box is a social phenomenon, for me it is a problem.” Ulrichs, David, ‘David Claerbout. Q/A, in: Modern Painters, May 2011, pp. 64-66

+++

“Time is invested into something that will prove to be valuable and productive. By consequence duration’ becomes increasingly expensive. But duration can only be free if it is unproductive.”

+++

“Cinema, YouTube and film-festivals demand the prolonged physical immobility of the viewer. Music, exhibitions or a walk in the park don’t.“

My sense of being in limbo stems from a hesitation: to move further into abstraction rather than figuration, toward longer forms rather than shorter ones, toward meditative sound and video landscapes rather than straightforward documentary. It also comes from my struggle to resist the banality of social media—where time is squandered on addictive, bite-sized fragments of content that ultimately feel useless.

I believe I know the answer, yet I dare not leap just yet.

Who will be the one to give me a gentle nudge?

Is this still needed?